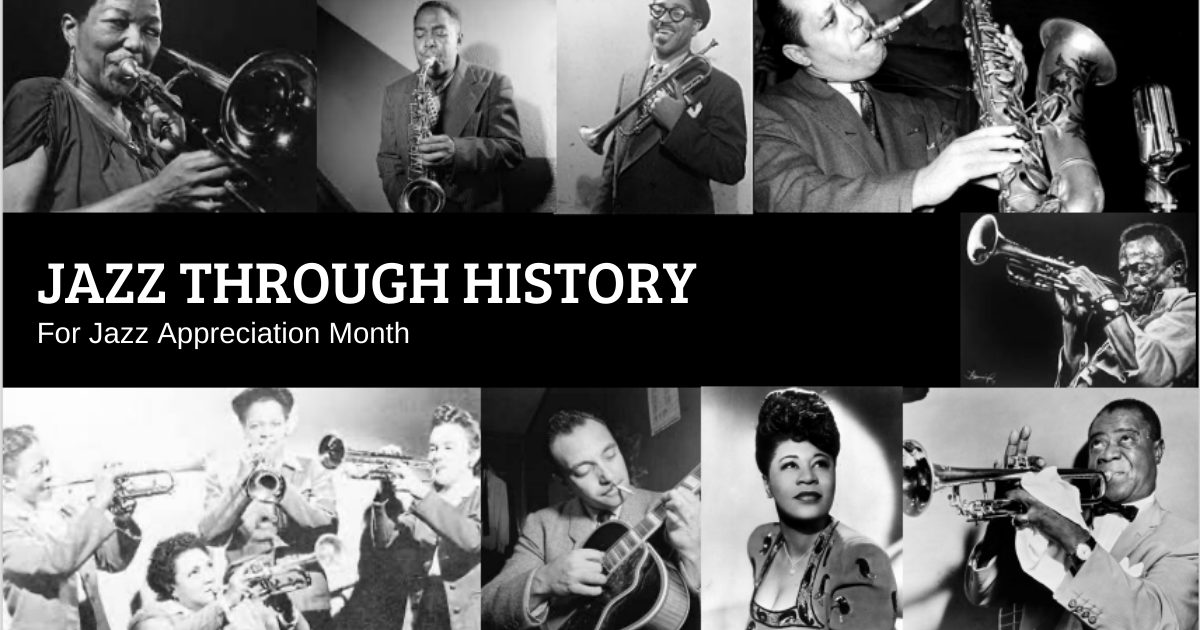

Jazz through History, for Jazz Appreciation Month

April is our favorite month of the year – why? It’s Jazz Appreciation Month! This year, we’d like to mark this month with a look back at key moments in jazz history. To be fair, there are hundreds of artists, and many memorable eras in jazz, so this is only the tip of the iceberg. But if you’d like the sky-high view, we’ll share a few highlights from its beginning to now. These tidbits are courtesy of Dr. Kelsey Klotz’s Jazz 101 Workshop, JazzArts Spring Adult Workshop offering.

This is all being shared on social media so feel free to watch the evolution unfold there as well.

19th CENTURY, PREJAZZ: African work songs, field hollers, and spirituals are widely considered a folk origin of jazz. They are marked with lose rhythm and syncopation, individually expressive, and spirituals often add harmonic elements plus call and response. “The Buzzard Lope” Georgia Sea Island Singers: a spiritual dance with African origins.

EARLY 1900s, THE BLUES: Blues is a prominent influence on jazz, and we’ll see its importance continue throughout jazz history (in musical approach, blue notes, blues form, and emphasis on improvisation) “Reckless Blues”, features prominent artist Bessie Smith singing the typical 12 bar blues formula and call and response.

EARLY 1900s, NEW ORLEANS: As a port city, there was more flexibility for cultures to intertwine and share their musical traditions. The downtown Creole population had more access to education and classical genres, while African Americans in Uptown emphasized more improvisation. “Livery Stable Blues”, Original Dixieland Jazz Band: This all white band is the first recording of New Orleans style jazz, Dixieland, codifying the music. You can hear the mixing of musical styles in this polyphonic genre.

1920s, THE GREAT MIGRATION: The African American culture and this new music spreads to NY, Chicago, Philadelphia, Detroit- now known as jazz cities. Chicago style jazz established the blues scale, and shifted from a polyphonic sound to individual instruments taking turns with virtuosic solos. “West End Blues”, 1928, originally by Joe King Oliver, then recorded by Louis Armstrong.

1920s, PAUL WHITEMAN: Becomes known as “king of jazz”. This white musician was seen by white audiences and critics as putting respectability to the music, by creating more formal arrangements. This evolution resulted in this version being the most broadly circulated of the time, both in the US and abroad. “An Experiment in Modern Music”, Paul Whiteman Orchestra & George Gershwin Rhapsody in Blue 1924.

1930s, GREAT DEPRESSION: Record sales plummeted. To fill a need for something uplifting, swing jazz with big bands was born and developed into the popular live music of the day, played in dance halls. “King Porter Stomp”, arranged by Fletcher Henderson, composer Jelly Roll Morton, Benny Goodman Orchestra, 1935.

1930s, TERRITORY BANDS: The shift to live dance music in the 1930s gave rise to Territory Bands that took the music beyond the major cities. Prevalent in the West and Midwest, these bands would eke out a living as local musicians who toured within driving distance. “Until the Real Thing Comes Along”, Andy Kirk and The Twelve Clouds of Joy, 1936. – #1 on pop charts, arranged by Mary Lou Williams.

1940s, BEBOP: With the onset of WWII, black musicians were tired of the hypocrisy of segregation at home in the swing scene, and so evolved their music away from “popular” and toward a more personal sense of expression and accomplishment. This bebop era is marked with fast dense tempos and highly complicated melodies and harmonies. “Ko Ko”, 1945, with Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker.

1940s, SCAT: Vocalists of the 1940s bebop era demonstrated those same instrumental elements of bebop – improvisation through scat, plus rhythmic and melodic speed and complexity. “Blue Skies”, Ella Fitzgerald.

1950s, COOL JAZZ AND MUCH MORE: The popularity of cool jazz and hard bop seemed to magnify musical, regional, and racial differences between musicians. Cool jazz musicians favored moderate tempos, dynamics, and melodic ranges, while hard bop musicians leaned into rhythmic intensity, heavier timbres, and assertive accents. Compare Modern Jazz Quartet, “Vendôme” and Clifford Brown, “Joy Spring”.

1950s, JAZZING THE CLASSICS: Though sometimes dismissed by jazz musicians as too commercial, musicians who combined jazz and classical music were typically highly proficient in both genres. “Black & White are beautiful”, Hazel Scott from the 1943 film, The Heat’s On.

1960s, CIVIL RIGHTS: This year the National Museum of American History’s Jazz Appreciation Month is officially recognizing Nina Simone as representative of women and jazz’s contribution to civil rights. 1964’s Nina Simone in Concert famously addressed racial inequality and her 1964 performance of “Mississippi Goddam” was selected as culturally and historically significant by the Library of Congress.

1960S, JAZZ PIANO: Bill Evans (1929-1980) helped to change the sound of jazz piano in the late 1950s and early 1960s. The way he structured his chords (his voicings) around open-ended and extended harmonies continue to be popular for jazz pianists today. Also, he reformatted the traditional jazz piano trio—while for earlier pianists like Art Tatum or Bud Powell the jazz piano trio was a vehicle to showcase the pianist, Evans’s trios were based more on the interaction between the bass, piano, and drums. “Waltz for Debby,” an Evans composition

1970s, FREE JAZZ: Ornette Coleman (1930-2015) was among the first jazz musicians to experiment with free jazz, or avant garde jazz. He defined his improvisational style as “harmolodic”: or improvisation in which melody, harmony, rhythm, and time are valued equally, leading to open expression. An early free jazz piece by Coleman is “Lonely Woman”, which begins with a slow bass dirge that is joined by fast drums. Then the saxophone and trumpet enter in unison with a melody full of bent notes and wailing sounds—they repeat this several times, including in between solos.

1970s, JAZZ ROCK FUSION: The 1970s are a decade in jazz marked especially by jazz-rock fusion, as jazz musicians were inspired by the new sounds and techniques of rock, and sought to make their sound relevant for the public. One of the most influential jazz-rock fusion bands was the Mahavishnu Orchestra, featuring John McLaughlin (b. 1942), which was known for loud, fast, and intensely distorted music. McLaughlin helped to push the virtuosic guitar techniques of Jimi Hendrix even further. “The Dance of Maya”

1970s, COSMIC SPIRITUALISM: Jazz musicians in the 1960s and 1970s were also highly influenced by the cosmic spiritualism that rose to prominence during this period. Alice Coltrane (1937-2007) worked with her husband John Coltrane on spiritual projects like A Love Supreme (1964) before moving even further into this vein after his death as a keyboardist, harpist, composer, and bandleader. In the 1970s, she is known for albums like Universal Consciousness (1971) and World Galaxy (1972). “The Ankh of Amen-Ra”

1980s JAZZ RENNAISANCE: The 1980s brought a renaissance in interest in jazz, and a split emerged between followers of neoclassical jazz and fusions between jazz and other musics (like pop and hip hop). The neoclassical approach, led by Wynton Marsalis (b. 1960), put forward a more conservative approach, returning to a canon of traditional jazz masterpieces (like New Orleans, Swing, and Bebop). Critics of this style felt that the style was too limiting, while proponents believed it afforded jazz the respect it deserved. In 1984 Marsalis became the first musician to win both the jazz and classical categories in the same year. “When You Wish Upon a Star”

1980s JAZZ HIP HOP FUSION: Not all jazz musicians in the 1980s wanted to look only to the past for inspiration. Herbie Hancock (b. 1940) desired the freedom to play in, out, and around the jazz canon (and to include more electronic instruments and effects). His 1983 composition “Rockit” became one of the first known jazz-hip hop fusions, and won a Grammy Award for Best R&B Instruments Performance. The subsequent video won five MTV Video Music Awards in 1984, and Hancock credited the success of the video with helping to get more Black artists featured on MTV.

1990s SMOOTH JAZZ: Smooth jazz is a genre that draws no lukewarm response: listeners usually either love it or hate it. Either way, smooth jazz, a commercially successful fusion of popular music and jazz with a hint of light R&B, was extremely popular among some audiences in the 1980s and 1990s. Kenny G (b. 1956) is one of the genre’s most commonly known musicians. But for those that may criticize smooth jazz artists, skip to 2:30 of his song “Songbird” to hear some virtuosic playing amidst the smooth melodies.

TODAY, COLLABORATION NEXT LEVEL: One of the most versatile musicians today is pianist Robert Glasper (b. 1978), whose 2013 Black Radio propelled him into crossover recognition, earning him a Grammy Award for Best R&B album. Glasper demonstrates a view of jazz as Black music that isn’t entrenched in boundaries, but rather borrows across genres. He collaborates with musicians like Lalah Hathaway, Erykah Badu, Yasiin Bey, Common, Jill Scott, Norah Jones, Snoop Dogg, and Kendrick Lamar. “Afro Blue,” featuring Erykah Badu, demonstrates this genre-mixing approach to jazz improvisation and collaboration on a jazz standard from 1959.

TODAY, CREATIVITY NEXT LEVEL: Creativity doesn’t begin to describe bassist and vocalist Esperanza Spalding (b. 1984). After she graduated from Berklee College of Music at just age 20, she became the youngest instructor in the school’s history. She won the Grammy Award for Best New Artist in 2010 (the first jazz musician to do so, and beating Justin Bieber), and since then, each album release has been a unique experience—from the smooth intimacy of Radio Music Society (2012) to the R&B fusion on Emily’s D+Evolution (2016) to the vulnerability on Exposure (2017) to thinking about new ways of framing music in 12 Little Spells (2018). Spalding, now a Harvard faculty member, is constantly thinking about and re-thinking what creativity means in jazz.

“Little Fly,” from Chamber Music Society (2010) &

“One,” from Emily’s D+Evolution

SO WHAT DO YOU THINK? Explore more during Jazz Appreciation Month at the National Museum of American History website, or by searching #jazzappreciationmonth on Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram and then add your thoughts on our social media pages.